As the COVID-19 virus continues to globally spread havoc, societies rise against social injustice, and climate change seeps further into our consciousness, we in the New Zealand wine industry are being confronted with and challenged out of our privileged position, in many ways. The focus and language of wine – and particularly fine wine – is shifting. Founded on fading customs and class divisions over the last 200 years, wine is instead becoming approachable. The wine aficionado is becoming classless by transcending traditional class dynamics with accessible language, visuals and inclusive social values. The wine industry itself will have to adapt quickly because underestimating the impact of shifting behavior and attitudes can have serious ramifications.

The evolution of societies is not simply a result of material growth. The development of human values and interconnectedness is transformational, as we are seeing now. The change in global psychic unity is breaking some of humanity’s existing customs, creating new divisions and redeveloping values in rapid fashion. If we are open to change, we can learn from evolving societies and grow with them; but the influence is neither one-dimensional nor one-directional, and the agricultural industry has an opportunity to reflect and influence also.

New Zealand’s society has come from the merging of indigenous Māori society with the sprawl of colonisation, and the immigration of (mostly) Europeans. If we are not Tangata Whenua (people of the land) we are Tangata Tiriti (people of the treaty), and the relationship between these peoples demands respect of and adherence to the basic principles of Te Tiriti o Waitangi: Partnership, Participation and Protection. These principles underpin every level of our (New Zealand) society, not least our workforces and industries, but also the very land we farm.

It is probably no surprise that wine is the product of agriculture; we farm the grapes to mine the soils, harvesting each year and following seasonal cycles. One could, therefore, argue that drinking wine is an agricultural act, and this train of thought inextricably links the wine drinker – you – to our values and approach to farming. One of our aims at Dry River is to ensure you feel good about drinking our wine: that when you open a bottle of Dry River, you know we actively honour the foundations of our society as laid out in the treaty, thereby continuing to look at how we can positively relate to our community, staff, the land we farm, and the sustainability of our business as a whole.

Here is a toast to feeling good through positive actions!

Thank you for believing in what we love.

Wilco and the team at Dry River

Vintage Preview

and Tasting Notes

Vintage 2020

There were many happy faces amongst the wine producers in Martinborough, up until mid-March. Then Covid-19 reached New Zealand and forced the country, and world, into an unprecedented lockdown, shutting down most of our professional and social lives and releasing a serious dose of stress and anxiety. It was an experience that will surely be with us for many years to come.

Many were lucky, but some didn’t escape so well. We were allowed to keep going, luckily, and able to finish the harvest. In any other year, the harvest is our time for celebration. The relief of harvesting many months of blood, sweat and stress. At picking time we have a community to help us, to share with us and to support us in this joyous occasion. Ordinarily we have a community to help us with harvest, but the lockdown meant the entire process was undertaken entirely by our small team. It was their determination, and the neighbourly camaraderie of others in our position, that got us through. A big thank you to all!!

Who will remember the 2020 harvest for anything else? Well, a brief reminder that the vintage was nothing but spectacular. After a frost affected the 2019 vintage, many vineyards this year seem to have recovered well. A cool spring was easily forgotten after the warm flowering conditions in December. This meant that the yields were healthy, combined with continued beautiful summer weather in January, February and March. So nothing was going to throw us out, nothing. Not even the rain event at the start of April, breaking the drought for most of the country south of Auckland.

2020 is promising to be a stellar year; one to remember, one for the books.

Air New Zealand

Fine Wine Programme

Rugby, kiwifruit, dairy, meat and Lord of the Rings are all great examples of products through which New Zealand has been able to proliferate itself around the world.

Air New Zealand has been a great supporter and champion of many New Zealand industries over the years. Countless travellers have been welcomed with a warm dose of Kiwi culture from the moment they board their plane to New Zealand.

Wine is another product for which New Zealand is becoming globally recognised. Recognising the growth of wine tourism for both national and international travellers, Air New Zealand developed the Fine Wines of New Zealand programme to showcase the best that this country has to offer.

The programme recognises that New Zealand produces a range of world-class wines renowned for their purity, vibrancy and unique characteristics. The aim, via an annual New Zealand-wide search, is to find “world-class quality and consistency – a high barrier to inclusion consisting of wine quality, wine pedigree and consistency”. It is a search for wines that can stand the test of time as world-class examples of New Zealand’s best.

We are thankful and proud that Dry River wines have featured every year since the programme’s inception in 2015. Our Pinot Noir, Pinot Gris, and Gewürztraminer are currently on the list of Fine Wines of New Zealand.

The list of wines is curated by seven of New Zealand’s leading wine experts — Masters of Wine Alastair Maling, Emma Jenkins, Michael Brajkovich, Sam Harrop, Simon Nash and Steve Smith, along with Master Sommelier Cameron Douglas. Their insight and long involvement in the New Zealand wine industry is paramount to recognising individuality on a world stage level.

Musing

FASHION, FLAVOUR

and Phenomenology

We are seeing new challenges to wine archetypes from a new generation of wine drinkers and the growing “natural wine” movement. Language and attitudes are becoming less formal, a change that is accelerating each year. Here, we have decided to re-publish an abridged version of a 2006 musing by Neil McCallum about the role of cultural perspectives in how wine is experienced. It is a topic that finds new resonance in this changing landscape.

The results of wine-shows and reviews by wine-writers are read by some aficionados as avidly as they would savour a bottle of wine. However, research indicates it is not physiologically possible to evaluate 100 or even 30 wines in a row for their purely aesthetic value and personality.

Two issues are involved; the first is palate fatigue, where the more wines that are tasted during an evaluation, the more influential the obvious features of a wine become – hence high alcohol and lots of new wood become common features of successful show wines even though this style of wine may be rather less welcome at the dinner table.

The second is that they are evaluated relative to an accepted judging norm and/or relative to the other members of the whole group of wines.

Nevertheless, wine commentaries and shows do have a well-earned and useful place. But if we take them to be definitive rather than as opinion, as we seem to be predisposed to do¹, we demean our distinctive ability to discriminate and assess according to our unique palate and to the culture in which it is educated. Slavishly following judging paradigms is likely to result in a fashion judgment rather than discernment and from the perspective of a grumpy old man, it is my perception that society has become much more fashion-conscious over the last two decades: in its clothes, its cars, the way it talks and behaves, the food it eats and now, even in the wine it drinks.

Fashion has several functions: it can be worn as a badge to denote your outlook, views or position in society. It can even reflect insecurity and prejudice or it can be just fun. It may also be regarded as a display of taste and discernment and it is here that we have the contradiction. Fashion is after all about national and even international conformity, and apart from the few who set the fashion, the danger in following other’s views is that of ignoring, repressing or even denigrating one’s own good taste and discernment as predetermined by our own culture and physiology. In this sense, fashion-following is a denial of self, whereas an individual’s holistic discernment is the core of civilised life and culture.

It is acceptable to claim that an objective discussion about objective discussions (about taking pleasure in wine) is a reasonable thing to do, but if we return to the situation that persists with wine commentators offering objective analysis of personal, subjective sensations of pleasure the situation looks intellectually rather more dodgy.

I have covered this subject in some detail in the article “The brain is a blunt instrument”, which includes quotes from Robert Dessaix, talking about the appreciation of beauty as the facility for “wonder” and that “we’ve been spiritually de-schooled by the kind of world we live in and the kind of values now dominant … this schooling is about efficiency, power … it’s important not to know everything if you want to have wonder”

In the ancient world, this conflict between knowledge and subjective experience did not seem to be a problem. God(s) and religion were also entangled with the world view but the difference between Kerygma (Greek: message or teaching) and Dogma (hidden tradition or experienced truth) was clearly understood and accepted.

In the religious sense, they were both described by Bishop Basil (329-379 AD) as being essential: he described Kerygma as the public teaching of the early church and Dogma representing the deeper meaning of (biblical) truth which can only be apprehended through experience and expressed in symbolic form.

In plain language, this is the difference between the intellectual attempts at the objective description and confronting the subjective experience first-hand. The first is something to read, even discuss and has the potential of being a guide. The second is direct and finally unfettered by knowledge, concepts or prejudgment.

The world changed with Isaac Newton in the 1670s. He believed all things followed a natural physical order and could be described objectively and completely in a mechanistic understanding. He succeeded magnificently in the physical sciences on this basis, and in doing so ushered in the Age of Reason with the assumptions that underpin rationalist argument even today. This is the logical source of the 19th century Industrial Revolution, and the incredible material sophistication of the 20th and 21st centuries

But it has had little relevance to the individual’s experience and appreciation of the arts and aesthetics. Seeds of the counter to this movement can be found before Bishop Basil, where the early mystics claimed the primacy of subjective experience (in God) mysteriously experienced in the “the ground of being”:

“[This] is to be approached through the imagination and can be seen as a kind of art form, akin to the other great artistic symbols that have expressed the ineffable mystery, beauty and value of life. Mystics have used music, dancing, poetry, fiction, stories, painting, sculpture and architecture to express this Reality that goes beyond concepts.”

– A Short History of God, Karen Armstrong, 1993.

Obviously, mysticism cannot be claimed to be “mainstream” today, but meditation, the route used by mystics for approaching the “ground of our being” has become so – be it acknowledged or otherwise. We now commonly talk about “grounded” individuals, the need to “let it go” and other concepts which clearly point to the adoption and secularisation of meditational tools and understanding in modern living.

All this is a philosophical partial retreat from objectivity. It is about finding a ‘new balance’ between the modern understanding of kerygma and dogma and how to achieve the frame of mind best suited to acquire the necessary ‘subjectivity’ for aesthetic experience. It is an acknowledgement of the need for a “phenomenological” view of life – I am referring to the philosophical tradition which started with Edmund Husserl (1859-1938) and which includes Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty and Jean-Paul Sartre. According to this view² it is the unique relationship between the taster and the wine which is tasted which sums up the experience and it is not possible to separate the two poles of the experience if it is to be truly represented. We owe it to ourselves to approach the pleasurable experience from beautiful wine with wonder and anticipation, without too much knowledge and definitely without prejudice.

¹In some interesting work done by the Virtual Reality Research Group at Oxford University a virtual reality room was designed that could grow or shrink as volunteers walked through it. It was found that even if they enlarged the room by up to four times its original size, subjects failed to notice. They faithfully reproduced all the visual cues that we normally use to judge size and distance – including binocular disparity and motion parallax – yet the volunteers disregarded them in the light of their knowledge based on previous experience that rooms just don’t do that. Conclusion: “If your sensory information is very specific, you’ll go with that … but if it’s poor or confusing, you’ll go with your prior assumption”. ²As Merleau-Ponty writes: The world is not problematical. The problem lies in our own inability to see what is there. The attitude of the phenomenologist, therefore, is not the attitude of the technician, with a bag of tools and methods … etc … Rather it is an attitude of wonder, of quiet inquisitive respect as one attempts to meet the world, to open a dialogue, to put himself in a position where the world will disclose itself to him in all its mystery and complexity.

Wılliam Wordsworth

William Wordsworth (1770 – 1850) was an English poet at the start of the Romantic Age in English literature. This year, 2020, marks the 250th anniversary of his birth.

This anniversary is something we want to highlight because, in 2019, several bottles of Dry River wines made their way into the Wordsworth Room at St. John’s College, Cambridge University. It was a tasting that was organised in association with the Cambridge University Wine Society and our UK distributor David Harvey.

Of particular interest to us is that, in his poems, Wordsmith lauded places and people usually not heard. In the cacophony of the wine world, this seems apt as a metaphor, where Burgundy, Bordeaux, Barolo and Champagne dominate the discourse. We are grateful to have had the opportunity to show our wines to the Society in collaboration under David Harvey’s guidance.

Together with Samuel Coleridge Taylor, William Wordsmith co-authored “The Lyrical Ballads”. According to David, the poem is a fitting reference to all of our wines, and he adds that “Wordsworth’s definition of poetry as ‘the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings’ is the kind of sensory overload experience you breed into your wines.”

This praise and connection prompted me to further research the works of Wordsworth. I discovered his rich collection of profound poems, and below we have re-published one depicting Wordsworth’s fondness of being moved by the beauty of nature, by the structure of things, of giving time to observation, and acknowledging the effects of human greed and neglect that destroy the natural world to which Wordsworth was so devoted in his work. It is a poem I, and the spirit of Dry River, can identify with.

Lines written in early spring

I heard a thousand blended notes,

While in a grove I sate reclined,

In that sweet mood when pleasant thoughts

Bring sad thoughts to the mind.

To her fair works did nature link

The human soul that through me ran;

And much it griev’d my heart to think

What man has made of man.

Through primrose-tufts, in that sweet bower,

The periwinkle trail’d its wreathes;

And ‘tis my faith that every flower

Enjoys the air it breathes.

The birds around me hopp’d and play’d:

Their thoughts I cannot measure,

But the least motion which they made,

It seem’d a thrill of pleasure.

The budding twigs spread out their fan,

To catch the breezy air;

And I must think, do all I can,

That there was pleasure there.

If I these thoughts may not prevent,

If such be of my creed the plan,

Have I not reason to lament

What man has made of man?

Profiles

El Molino Wines

St. Helena, California,

United States

Like for many of you, wine is our passion, one that we like to share with other wine aficionados. This platform gives us another opportunity to share our passion with you by highlighting a producer whose wines, practices and philosophies lie close to our hearts.

The first producer we would like to highlight is obvious to us. As we moved into the 21st century, Neil was looking to secure Dry River’s future. This future, and the potential of Dry River Wines today, was greatly influenced by the vision of one man: Reginald Oliver.

Reg, a close business associate of our owner Julian Robertson, travelled through New Zealand in 2003 with his daughter Lily. During the trip, they stumbled upon Dry River after hearing a rumour it was for sale. They discovered that Dry River Wines was almost an exact copy of their family vineyard & winery, El Molino Wines in California’s Napa Valley, reflecting similar values. Shortly after, Julian and Reg decided to partner up and acquire the estate.

To discover Reg’s passion and motivation, we have to rewind the clock almost 150 years and move to the United States. In 1871 El Molino Wines was founded as one of the first wineries in Napa, and it remains family-owned and operated to date. In its long history, El Molino produced a plethora of wines from different varieties, but from the early 1980s, Reg Oliver settled on producing Chardonnay and Pinot Noir. This was a decision against the odds but, like for many visionaries, one that paid its dividend over time.

Nowadays, the fresh eyes and hands of Reg’s daughter Lily and partner John Berlin are at the helm of the business, further developing his vision. They have renewed the family’s love affair with the estate and through their devotion and tenacity continue to produce incredibly gorgeous Chardonnay and Pinot Noir, reaching unexpected heights of finesse and tension in their wines. Their passion and affection for their vineyards, wine and the business permeate each bottle. You drink their time, without a doubt.

It is through this historical connection that a small collection of their wines is still hidden away in our cellar, ageing gracefully, and enjoyed when their time is right.

We admire you, Lily and John, for living on your legacy!

Arentz Wines

Nijmegen,

the Netherlands

Nijmegen is probably (and unrightfully) an unlikely place to visit during your travels in Europe. It is one of the four oldest cities in the Netherlands, indeed older than Amsterdam, with Roman settlement records dating back to 1st century BC.

Strategically situated between the rivers Mosel and Rhine, Nijmegen gained power through trade, and the Romans used Nijmegen as a tactical settlement for nearly 500 years until the Frankish Empire gained power. The flipside of this meant it also has been a victim of numerous battles, including during the Spanish war, the Franco-Prussian war, and it was the end station of World War II’s “Operation Market Garden” (as depicted in the movie A Bridge Too Far).

Nowadays Nijmegen and its surroundings are a fantastic “off the beaten track” destination to discover. There are beautiful treasures everywhere in and around Nijmegen, including a treasure for wine lovers: Marcel Arentz Wines.

Inspiration and motivation are two important traits a mentor may represent, either deliberately or unconsciously, to their mentee. Furthermore, a mentor may also act as a role model thanks to their personality, social and professional position.

Marcel Arentz has had this influence on me. He infected me (wittingly) with his wine bug. His love for wine and profuse passion for German Riesling and Burgundy are contagious to anyone entering his domain. Marcel certainly has had a lasting impact on me, especially his appreciation for the significance of history and relationships, important aspects of the wine trade.

Perhaps more significantly, he knows that wine is for everybody, that there is a wine for everyone. In my brief time working in his wine business – his world – he showed that this passion is rooted deeply. It’s his passion that has helped keep people connected and valued as customers, who subsequently return to him and keep him in business.

Bravo, Marcel, for your endless positivity!

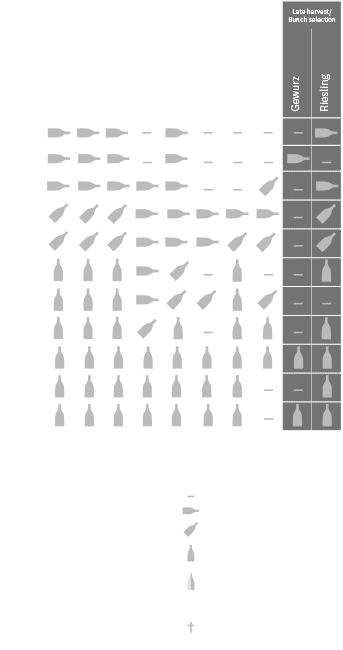

Cellaring guide

Be aware that our wines can ‘go into a tunnel’ somewhere between six months and two years after release. During this time the wine can be quite unrewarding, but be patient because it can blossom later and confound earlier impressions and predictions. A second dip can occur between 4 & 6 years when the wine can start to look tired then may well emerge looking refreshed and in an interesting new phase for the next few years. It can be worth opening and even decanting them a few hours before serving – particularly the reds.

THE EFFECT OF CELLARING CONDITIONS ON YOUR WINE

Warmer and fluctuating temperatures will age wine more rapidly and may not be as beneficial to the less robust wines and varietals. In our experience the ‘robustness’ of wines is likely to be in the order: Cabernet and blends > Sauvignon blanc > Syrah > Riesling > Pinot gris and Chardonnay > Pinot noir and Gewurztraminer. Wines high in extract will tend to mature rather more slowly than the ‘average’ same varietal on this list. If you have a number of our wines and your cellar conditions are not similar to our ‘standard cellar’, you will no doubt learn how to interpret the chart in relation to your own conditions. However, a more active approach to evaluating your cellar is to note temperatures for the range of the days, between weeks and between seasons, by leaving a thermometer in a large jar of water in your cellar. It is not sufficient to observe that the cellar ‘always feels cool’ – such feelings are relative only to outside conditions. Significant fluctuations in daily or weekly temperatures tend to add to the speed of ageing commented on below, and may also increase the incidence of leakers and seepers, occasionally give examples of ATA (atypical ageing – see Aromas) and disproportionately fast ageing for laccase-containing wines (i.e. those with potential or actual botrytis). Vibration and direct light on the wine are damaging influences which should also be avoided.

General Notes Relating to Cellared Wines

Wine maturation is an organic process which is very dependent on the conditions of cellaring. Wines do not inevitably end up at a predictable quality and style, hence André Simone’s famous quote ‘there are no great wines, only great bottles.’ Nevertheless, cellars with the best possible conditions are the most likely to produce the best possible end results.