10th February 2017

After an inspiring week in Wellington at the Pinot Noir NZ 2017 Conference, hearing individuals leading the industry in organic vineyard farming practices, I thought it was time to share our story.

Dry River has been slowly shifting towards an organic regime for some time now. The canopy and disease management have always predominantly been organic, it has been the undervine weed competition and herbicide use that needed to be addressed. We’ve been ready for the change for a long time, and with the arrival of the under vine cultivator at the end of 2016 the reality of organic farming is starting to take shape. We have been able to cease using the herbicide’s and begin mechanical weed control. In a normal organic conversion, you would expect a lot more competition from weeds while they fight to get the weeds under control, but with our machine it does such a good job that that hasn’t yet been an issue.

Wandering through the vineyard now, to a visitor that frequents Dry River the most visible change would be that no more are there neatly trimmed lawns between rows. You are now more likely to see shoots and leaves between the vines, with flowers reaching halfway up the trellis height. These are filled out with oats, clovers, mustards, rye grass, radish, a rejuvenation process for the soil, with each plant bringing a different property.

Nick James, our long standing vineyard manager here at Dry River up until September last year, was instrumental in this shift. I spoke to him before he left, and he filled me in on the properties that each plant brings to the soil. “The oats bring in some extra organic matter, growing quickly to pave the way for other crops to grow. The clover is very good for fixing nitrogen, the radish and mustard are quite deep rooting so they break up the soil structure and compaction and the ryegrass reduces the leaching of soil nitrogen. In spring, we plant flowers, the idea there is to attract a wide variety of insects to try and control parasitic insects that live on the vines. We had a soil specialist come and visit us, guiding us through the planting.”

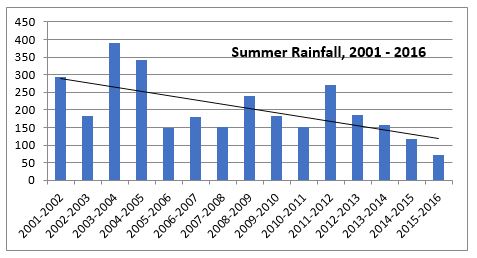

Nick went on to discuss the changes he has seen in climate over the time he spent at Dry River “I don’t think the temperatures are necessarily increasing that rapidly but when I looked back at the time period from 1909 through to 1920, they were averaging around 220mls of rain per summer, November through to February. You then fast forward to the 80’s and you are down to around 195mls. With this there is also a lot of instability, you have very very dry years, followed by very very wet years. Fast forward again to now and you see two big flood years then every year is basically a drought. There no longer seems to be the replenishment happening. In the earlier years I looked at, if you put a trendline on the graph following seasonal rainfall, you ‘d see the start of the century is basically level. Fast forward and you have an up/down pattern, but for the last 15 years it’s basically plummeting. Similarly, if you take the total yearly rainfall and graph it over the last 50 years, it’s just a continual drop. We can no longer count on rainfall being reliable. We can’t count on 200mls of rain, you have to get used to dealing with 100mls or 150mls.”

Nick wasn’t at Dry River to view the 2017 season first hand, which I have heard coined the un-summer in this greater Wellington region. With 190mls of rain for the summer season by the end of January alone, this will definitely impact the graph above, and more importantly the soils below. But is this enough to provide any long-term results?

We have explored the use of drought resistant root stock here at Dry River. The Dry River Pinot Noir block is a clone of rootstock called 5BB, and those are big strong vines, which might be quite drought tolerant. Otherwise we are limited to what root stocks are available to us. In answer to this we keep our focus on managing the pruning, how many buds we lay, which equals how much fruit we get and how much canopy growth. Those are the tools we have at our disposal, unless we want to install irrigation which for us is not an option.

It is definitely a journey, one that we are committed to follow through. Not only does an organic vineyard make for a safer environment for the people that live and work here, it means we are producing wine free of agricultural chemicals, showing a true expression of the land in which it is grown.

View our latest release here